RAF Kinloss 236 OCU 1948 ~ 1950

W/C A J L Craig – Posting

RAF 236 OCU Kinloss

16th June 1948 to 3rd August 1950

W/C & Chief Flying Instructor (Age 25-27)

Operational Conversion Units

After surviving his 1st Tour in Bomber Command Hamish Mahaddie was, in July 1940, assigned Officer Instructor at RAF Kinloss in Scotland. He served with No.19 OTU RAF, still flying the Whitely. The goal at Kinloss was to take Pilots, Navigators, Wireless Operators, Bomb Aimers & Air-gunners, all arriving from their respective Basic Training Stations, and sort themselves out into Crews of 5, before starting their 12 to 14 weeks course of Operational Training. Mahaddie worked to meld them together into functioning Crews. He proved to be excellent at Training Crews, and over the next 2 years, he rose to the rank of Squadron Leader. Frustrated in no longer flying Combat Missions, Pilots who returned to visit whom he had trained gave him the sense that things in the Operational Squadrons had changed since he had last been flying Ops. For his service at Kinloss, he was awarded the Air Force Cross (AFC), a non-combat Award that Mahaddie sarcastically referred to it as his “Avoiding Flak Cross.

With the drawdown in the size of the RAF towards the end and after WW2, the need for new Aircrew reduced dramatically and The OTUs were gradually reduced in size and many were disbanded. However, the concept had proved its worth and it was decided to continue the idea of separating type conversion & crew familiarisation from Operational activities and OCUs were established. These were of Squadron size and each unit trained crews for a specific aircraft or role. Final training is still carried out on the squadron but it can be more specifically aimed at squadron operating techniques rather than type conversion. Many OCUs were allocated ‘Shadow‘ Squadron designations in order to keep Squadrons of the Line alive and in time of war they would have operated under these squadron designations. Like Squadrons, they were commanded by Officers holding the appointment of Officer Commanding. Some of these units later changed their designations to indicate more clearly their actual role or new units were formed with named rather than numbered designations

Alan J Laird Craig DSO DFC AFC

Flying Wing 236 OCU Kinloss 16th June 1948 to 3rd August 1950 –

(on his return from Buenos Aries where he was Assistant Air Attache)

S/L Craig was Stationed at RAF Kinloss for 14 Months with his wife, eldest son Gavin and his daughter Diana who was born during this Posting at The Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford. His wife Mary had returned home to Knaphill for the Birth.

RAF Kinloss is a station near Kinloss, on the Moray Firth in the North of Scotland. It opened on 1st April 1939 and served as an RAF Training Establishment during WWII. After the War, it was handed over to Coastal Command to watch over Russian Ships &d Submarines in the Norwegian Sea. Kinloss also housed an Operational Maritime Squadron from December 1950 onwards, this being No.120 Squadron equipped initially with Lancasters, until replacing them with Shackletons. This Squadron remained here until departing for Aldergrove on the 1st of April 1952. Until 2010 it was the Main Base for the RAF’s Fleet of Nimrod MR2 Maritime Patrol Aircraft.

Not long after VE Day, 19 OTU was disbanded and the arrival of 6 Coastal OTU saw the beginning of Kinloss’s association with Maritime Operations, an association that continues to this day. The Wartime Avro Lancaster was adapted without great upheaval for anti-submarine and search & rescue duties and RAF Kinloss changed from a Bomber Training Unit to a Coastal Command Base training Maritime Aircrew. Its personnel now also included National Servicemen. 19 (C)OTU was split into No. 236 Operational Conversion Unit RAF and the School of Maritime Reconnaissance in 1947 with 236 OCU remaining at Kinloss.

S/L Alan J Laird Craig DSO, DFC, AFC as Chief Flying Instructor, Long Range Marine Reconnaissance, Air Sea Rescue, Instrument Flying.

Performance – ‘Above Average’

RAF Bircham Newton

Craig also attended an Officers’ Advanced Training School (OATS) Course in the post-war period at RAF Bircham Newton, Norfolk between March & May 1949 with no flying undertaken during that period. Technical Training Command took over this Station and it became the home of the Officers’ Advanced Training School (OATS), later to be renamed the ‘Junior Command & Staff School’ (JCSS). In October 1948 the Station was transferred to Technical Training Command and became the School of Administration, with the Junior Command & Staff School and the Administrative Apprentice Training School (AATS) also being based here from the late 1950s until 1962. The by far largest and most impressive structures on every Airfield are the Aircraft Hangars, and RAF Bircham Newton is no exception. The Aerodrome’s 3 C-type hangars, the largest Hangar type ever constructed by the RAF, are still in place. Measuring 45 x 95 x 11 metres (150 x 300 x 35ft) and designed to accommodate large Aircraft such as Heavy Bombers. The C-type Hangers are perhaps the most famous of all Hangars, and several variants in construction & appearance existed. The basic structure of these gigantic buildings comprises a steel shell, with steel stanchions supporting a steel-framed roof. The Hangars at RAF Bircham Newton are currently used for a variety of Training Projects for the Students of the Construction College, who have added their own Structures such as a couple of very tall chimneys which can be seen from quite some distance away.

Kinloss Training Flight 1943 – Contemporary Account

Our Aircraft was fitted with the same set up used by Bomber Command on their nightly raids, a photo flash linked to a camera and the bomb release button to obtain a photograph of the Target and the bomb pattern. All Training Crews on this flight had just the one photo flash, one chance to get it right. We were lucky that night because as we droned west the build-up of cumulus clouds over the Scottish mountains gradually dispersed and we were able to take Astro shots which helped us to confirm our position, and as the clouds thinned it also revealed a thin, melon slice section of the moon. We were able to fly towards the moonlight, dim though it was, and silhouette Rockall in all it’s craggy glory (270 miles) North-west of Ireland. We made our Bombing or Photograph run, Les pressed the button and we had that solid lump of rock plumb in the middle of the frame. It was very good Teamwork. From Rockall, we headed South-east for Mull Island and back to Base for the final flare Target Bombing and the North Sea shootout. For that trip, we were awarded full marks and each member of the crew received a photograph of Rockall. I still have mine, somewhere!

That was the last time we flew from Kinloss as a Trainee Crew. We completed the Station Commanders test, and then we were fully qualified for Bomber Command, Would it be Lancasters or Halifax’s? Our grading was quite good and we felt confident it would be Lancs. the ultimate in our view. However, in the RAF you were never sure what would be printed on the DROs (Daily Routine & Posting Orders). Like all the other Crews we had to wait and see and keep our fingers crossed. After a few days, the postings came through and we thought “a dead-loss” until we met the men of the 1st Airborne. Although fully qualified for Bomber Command, being typically British, the “powers that be” decided that our group of 24 Crews would be essential to develop 38 Group, the rapidly expanding Airborne Division.

Unfortunately, the new Training Squadrons were fully manned so we would have to wait our turn and instead of doing the sensible thing and sending us home on indefinite leave! We were posted to the Driffield Battle School in Yorkshire to train for 3 solid months, (1st November – 26th January) With the Commando and Airborne Divisions. (I thought it was much longer than that but those dates are in my logbook.) We thought we were fit until we met the 1st Airborne, then we found out we were not very fit at all. Mind you 3 months later, things had changed. We were fit, a young Commando Captain had made sure of that (the 1st human dynamo I had ever met) in fact you could say without any exaggeration that we were very, very fit, with muscles that bulged in every direction. We could toss tree trunks around, climb sheer Quarry walls, abseil down cliffs, cover rocky ground on elbows and knees with controlled machine-gun fire to keep our heads down, and thunder flashes to liven things up. We had to admit whether we liked it or not, the Airborne had done their best to make us feel at home and mould us into one of them.

236 OCU – RAF Kinloss – Loss of Avro Lancaster ASRlll 683 – SW363

Crashed on 12th January 1950

Took off from RAF Kinloss at 23.26, and crashed into ploughed field 2 miles from Forres. stated that the Aircraft was seen to be on fire soon after take-off but no definitive cause for the Crash was established though the Crew had reported a strong smell of petrol on a previous flight. 2 miles SSW of RAF Kinloss, Morayshire, Scotland

RAF Kinloss Involvement in the HMS Truculent Incident

Moving back to the day of the accident, there were 5 more casualties – the crew of a RAF Lancaster in Scotland which crashed in flames shortly after take-off. When the ‘Sub-Smash’ procedure was initiated after reports of the sinking of HMS Truculent reached the Admiralty, all units that were able or likely to assist in the rescue operation were contacted – this included RAF & Army Units. Naval Divers were needed urgently, and although HMS Reclaim (the dedicated Submarine Salvage & Rescue Vessel) was laid up in Portsmouth while undergoing maintenance, her Divers set out immediately for Kent. Other Divers were set to assemble at RAF Leuchars in Scotland, and Transport to the South of England was required urgently. By a strange twist, an anti-submarine warfare squadron based at RAF Kinloss was selected to pick up the Naval personnel and take them to Kent – a role reversal for Crews trained to seek out and destroy Submarines. At No.236 Operational Conversion Unit, a fast turn-around was ordered on Lancaster SW363 which was returning to Kinloss from a Training Mission, and a replacement Crew for the Flight was chosen.

The urgently picked crew for Lancaster SW363 was made up of highly experienced Officers and men who had been selected for their extreme competence and abilities – each was an Instructor in his chosen field, and between them, they had the experience and knowledge to carry out the task allocated to them successfully. Due to their positions as Instructors, they were ‘self-briefed‘ before take-off. It was probably unfortunate that on the night of 12th January 1950, when the call came through to find an Aircraft and Crew to ferry Naval Divers from Leuchars to Manston to take part in the rescue efforts for HMS Truculent, all of the Officers had been attending a ‘Dining in‘ night at Kinloss. Although each Officer had been drinking, the Board of Inquiry that followed the crash examined the Mess returns for the evening and decided that no Officer had drunk more than 4 sherrys and that therefore alcohol played no part in the accident. Although in today’s society, driving a Car after drinking 4 sherry’s would undoubtedly lead to complications. Most agree with the Board of Inquiry – the time between the Mess Event and take off, combined with the competence of the Crew and the urgency of their mission, would have left them clear-headed and up to their task. The fault that caused the mid-air fire was certainly beyond their control, and the Officers at the controls of the Lancaster had only seconds to react. Although the Fire Extinguishers hadn’t been triggered, everything else showed that they attempted an immediate ‘wheels-up’ landing.

Statement of Flying Officer Archibald Dick

“I am an Air Traffic Control Officer at RAF. Kinloss. I was on duty in the Control Tower at Kinloss on the night of 12th January 1950, at the time when Lancaster SW363 took off for Leuchars. I had been on duty in the Tower until proceeding to the Officers’ Mess for supper at the cessation of the night flying program. While in the Mess I was informed of the intended flights to Leuchars and Manston and returned to the Control Tower to make preparations for the Flight. I made arrangements for the “Homer” and the Crash Crew with vehicles to stand-by. As there was only one Aircraft to take off I did not consider it necessary to recall the Airfield Controller. I also switched on the Airfield obstruction lighting, perimeter track lighting, flare path on 21 runway and the appropriate funnel lights. I prepared a Flight Plan for my own information; the details of aircrew, aircraft, destination etc., I received from Sqn Ldr Craig the Chief Flying Instructor, who was arranging the Flight. For this intended Flight it was not necessary for the Captain of the Aircraft to prepare a Flight Plan, as he was not proceeding out of the United Kingdom, or into or through, a Control Zone. When the Aircraft was about to Taxi, I sent the

“I am an Air Traffic Control Officer at RAF. Kinloss. I was on duty in the Control Tower at Kinloss on the night of 12th January 1950, at the time when Lancaster SW363 took off for Leuchars. I had been on duty in the Tower until proceeding to the Officers’ Mess for supper at the cessation of the night flying program. While in the Mess I was informed of the intended flights to Leuchars and Manston and returned to the Control Tower to make preparations for the Flight. I made arrangements for the “Homer” and the Crash Crew with vehicles to stand-by. As there was only one Aircraft to take off I did not consider it necessary to recall the Airfield Controller. I also switched on the Airfield obstruction lighting, perimeter track lighting, flare path on 21 runway and the appropriate funnel lights. I prepared a Flight Plan for my own information; the details of aircrew, aircraft, destination etc., I received from Sqn Ldr Craig the Chief Flying Instructor, who was arranging the Flight. For this intended Flight it was not necessary for the Captain of the Aircraft to prepare a Flight Plan, as he was not proceeding out of the United Kingdom, or into or through, a Control Zone. When the Aircraft was about to Taxi, I sent the  Crash Tenders and Crews out to the take-off end of the 21 Runway. The Aircraft taxied out after receiving taxiing instructions from me, and with the normal delay required for Pilots checks prior to take-off, the Pilot received take-off clearance and took off at 23.26 hrs. When Airborne the Pilot called “Airborne” on the Radio Telegraph and was given the Northern Scottish Regional QFF which he acknowledged. No further contact was made with the Aircraft. I now produce a certified copy of the R/T Operators Log (Exhibit “A”) and I wish to draw attention to the discrepancy of 2 minutes between this log and my record. It transpired that the R/T Operators watch was 2 minutes slow. I did not see the Aircraft after it became airborne, nor did I see it crash. I then despatched the Crash Tenders and Ambulance to the scene of the crash.”

Crash Tenders and Crews out to the take-off end of the 21 Runway. The Aircraft taxied out after receiving taxiing instructions from me, and with the normal delay required for Pilots checks prior to take-off, the Pilot received take-off clearance and took off at 23.26 hrs. When Airborne the Pilot called “Airborne” on the Radio Telegraph and was given the Northern Scottish Regional QFF which he acknowledged. No further contact was made with the Aircraft. I now produce a certified copy of the R/T Operators Log (Exhibit “A”) and I wish to draw attention to the discrepancy of 2 minutes between this log and my record. It transpired that the R/T Operators watch was 2 minutes slow. I did not see the Aircraft after it became airborne, nor did I see it crash. I then despatched the Crash Tenders and Ambulance to the scene of the crash.”

Statement of Squadron Leader Alan John Laird Craig

“I am Chief Flying Instructor at No.236 OCU, RAF Kinloss. On the evening of 12th January 1950, I was present at a ‘Dining-in Night‘. After the ‘Port‘ had been passed, I was advised by Wing Commander Holgate that the Station Commander had excused my further attendance at the table since the OCU had been ordered to Stand-by a Crew to fly on a special Sortie that night. He asked me to choose a Crew for a possible flight in a Lancaster from Kinloss to Manston via Leuchars and return. I left the Dining Room and warned the Officer in Charge of Night Flying to prepare an Aircraft for such a Flight, and started to consider the selection of a Crew. At this time, the Dinner concluded and I was joined at the Telephone in the Hall by Wg Cdr Holgate, and several of my Flying Instructors. We were then informed that the purpose of the Flight was to ferry 12 Naval Divers and their equipment from Leuchars to Manston for rescue work in connection with ‘HMS Truculent’. There were many volunteers to form the Crew of the Aircraft, and I selected Flt Lt Harris as Captain, Flt Lt Williams as Co-pilot & Flt Lt Stevens as Flight Engineer. This selection was approved by Wg Cdr Holgate.

“I am Chief Flying Instructor at No.236 OCU, RAF Kinloss. On the evening of 12th January 1950, I was present at a ‘Dining-in Night‘. After the ‘Port‘ had been passed, I was advised by Wing Commander Holgate that the Station Commander had excused my further attendance at the table since the OCU had been ordered to Stand-by a Crew to fly on a special Sortie that night. He asked me to choose a Crew for a possible flight in a Lancaster from Kinloss to Manston via Leuchars and return. I left the Dining Room and warned the Officer in Charge of Night Flying to prepare an Aircraft for such a Flight, and started to consider the selection of a Crew. At this time, the Dinner concluded and I was joined at the Telephone in the Hall by Wg Cdr Holgate, and several of my Flying Instructors. We were then informed that the purpose of the Flight was to ferry 12 Naval Divers and their equipment from Leuchars to Manston for rescue work in connection with ‘HMS Truculent’. There were many volunteers to form the Crew of the Aircraft, and I selected Flt Lt Harris as Captain, Flt Lt Williams as Co-pilot & Flt Lt Stevens as Flight Engineer. This selection was approved by Wg Cdr Holgate.

Nav II Cunningham & Signaller I Geal were selected by the Leaders of their Sections. The Crew members had been selected because of their ability, experience and fitness to carry out this particular Flight. About this time information was received from Wg Cdr Holgate that the Aircraft should take off as soon as possible for Leuchars. The detailed Crew dispersed to prepare themselves for the Flight. I remained at the Telephone in the Mess to make further administrative arrangements, such as Parachutes for the Divers and victuals for the Crew & Passengers etc. When these were completed I left the Mess intending to go to the Hangar in my Car to see the Aircraft off. As I opened the door of my Car, I heard the Aircraft Engines ‘rev up’, and reflected as to whether the Engines were being test-run, or being opened up for take-off. In a few seconds, it was clear to me that the Aircraft was taking off. Knowing that No.21 Runway was in use I decided to remain by my car to watch the final stages of the take-off over the trees at the windward end of 21 Runway. No. 21 Runway is not normally used for Flying Training, since the trees at the windward end of the runway make a gradient of obstruction equivalent to 1 in 27 instead of the regulation maximum gradient for obstructions of 1 in 50. I saw the Aircraft clear the 1st trees by about 50ft and climb steadily away in a perfectly normal manner. I last observed the Aircraft at between 300 & 400ft before getting into my car. I started the Car, backed out of its parking position, drove in front of the Mess, a distance of about 30 yards, and intended to proceed to the Hangar to check administrative details such as ‘Duty Crew’ for their return. As I was turning away from the Mess, my attention was attracted by a steady and increasing ‘bright yellow-orange glow‘ in the sky. I stopped the Car, opened the door, and got out, whilst continuing to watch the glow. Almost immediately I heard the Engines ‘whine’ as though going into ‘fine pitch’ under increased power. Within 2 or 3 seconds there was a cut in noise as if the Engines had been throttled fully back, or cut. Approximately 3 seconds afterwards I saw an explosion of flame & smoke, and heard after a few seconds the noise of the Crash. In conclusion, I have retimed my actions from the stage when I first saw the glow in the sky, to the time when I saw the explosion in the ground, and estimate that this time interval was ’10 seconds’, and so assessed by the Court.”

Statement of Flt Lt William Howie

“I am the Senior Medical Officer at RAF Kinloss. At about 23.50 I saw a light in the sky after hearing an Aircraft take off. I phoned Air Traffic Control and had permission to take the Crash Ambulance to the Crash, from the Duty Control Officer. I arrived at the Crash accompanied by Flt Off Clark who is also a Medical Officer at RAF Kinloss, and the Duty Orderly. We were summoned 1st to Flt Lt Harris who was severely injured but still alive, we carried him into the Ambulance where he died 3 minutes later, from multiple injuries & shock. We then saw Flt Lt Stevens & Williams who were lying forward and slightly to the right of the main Wreckage, both were dead. Flt Lt Stevens died from multiple injuries and Flt Lt Williams from severe burns. Signaller I Geal who was lying slightly to the rear of the main Wreckage was also dead from multiple injuries. Navigator II Cunningham was found next morning under the Port Main-plane. I consider that he was killed at the time of the crash, and died from a fractured skull & other injuries. The bodies were conveyed to the Mortuary at Station Sick Quarters, RAF Kinloss.”

Statement of AC-I Leslie Kennard

“I am an AC-l Engine Assistant in 236 OCU, RAF Kinloss employed in Flying Servicing Section. On the night of 12th January 1950, I was on the Night Flying Duties in my Section, and at approximately 22.10 hrs I was working in the Hangar and was called to the Duty NCO’s Office and instructed by Sgt Middleton to refuel Lancaster SW363 when it came into dispersal. Shortly afterwards the Aircraft arrived and within a few minutes, the Petrol Bowser arrived at the Aircraft. I asked AC-II Brown another Engine assistant to help me refuel the Aircraft, which he did. I topped up tanks numbers 1 & 2, Port & Starboard, they were not permitted to overflow. I was actually in the main-plane, AC-ll Brown was on the ground by the Bowser, and Sgt Middleton was also on the ground by the Bowser, he was the Flight Duty NCO. After the tanks were topped up I replaced & locked the filler caps, but on replacing the filler cap of No.1 Port Tank, I found that the locking nut was unserviceable, that is to say, the lock-nut could be moved up & down, and would not tighten, I reported this to Sgt Middleton who came up on to the main-plane, and examined the lock-nut. Sgt Middleton gave me a 2BA plain nut to screw on top of the lock nut, which I did. I do not remember replacing the split pin, Sgt. Middleton supervised the fitting of the plain nut. I then replaced and secured the filler cap panel on top of the main plane.”

S tatement of AC-I Leslie Kennard (on being recalled)

tatement of AC-I Leslie Kennard (on being recalled)

“When I 1st attempted to screw the 2BA steel plain nut down on to the top of the locknut of the filler cap on No.1 Port Inner Tank, I found that I could not turn it sufficiently with my finger, because parts of the light-alloy thread of the locknut were embedded in the thread of the trunion bolt. I there-upon cleaned the thread with a mandrel off a pierced Rivet which I had in my pocket. This enabled me to tighten the 2BA nut down on to the light-alloy locknut with my fingers. As I had a set of Terry spanners in my pocket I used it and further tightened the 2BA nut approximately 2 full turns. I have read & signed as having understood all “Flight Orders” in my Section. I recall having read about 7 days ago, an order issued in relation to the Bending Sockets, situated near the Filler Cap on the Fuel Tanks. This to my knowledge is the only Order existing in strict relation to Filler Caps, but in the normal refuelling Orders, it stated that the Filler Caps must be secure. On tightening the 2BA nut with the Terry Spanner I do not consider that I overtightened the “Trunion bolt.” I was aware that these locknuts should not be overtightened, because on a previous occasion I overtightened one, and cracked the Filler Cap. This was during my Improver Course, and before I gained experience of working on Aircraft, and resulted in disciplinary action being taken against me.”

If anyone can provide the image referred to below please do so

5 crew members of Lancaster SW363. Back row L-R: Ernest Geal, Richard Gwynn Williams, John Cunningham. Front L-R: Leslie George Harris, Alfred Enos Stephens. Brief biographies as follows.

Sig 1 Ernest Geal – Service: Royal Air Force – Service Number: 615197

Unit: 236 OCU, RAF Kinloss

Date of Birth: 9th March 1916 – Date of Death: 12th January 1950

Buried: Cheadle Churchyard, Staffs

Sig 1 Ernest Geal (Wireless Operator) had 1st come to RAF Kinloss as a Student on one of the OCU courses. The high ability he showed during his Training, coupled with the obvious enthusiasm for his work, resulted in his being posted immediately to the Staff as an Instructor on completion of his Training Course. He was devoted to flying and although he had been offered other employment, nothing had been able to persuade him to leave the RAF. He had logged more flying hours than any other Instructor, over 3500, which was a remarkable record. It was noted that his keenness was always evident, and whenever a signaller was required he would invariably have been the 1st to volunteer for duty. When Lancaster SW.363 took off on the evening of January 12th, Sig.1. Ernest Geal was occupying the Wireless Operator‘s seat. At the crash site, his body was found to the rear of the main wreckage, and it was decided that he had died instantly from multiple injuries. Buried at Cheadle Churchyard, Staffordshire, Ernest Geal was survived by his wife and 4 children, 2 boys and 2 girls.

Flt Lt Richard Gwynn Williams – Service: Royal Air Force – Service Number: 166553

Unit: 236 OCU, RAF Kinloss

Date of Birth: 28th June 1924 – (Date of Death: 12th January 1950)

Buried: Kinloss Abbey, Kinloss

Flight Lieutenant Richard Gwynn Williams (known as Gwynn) joined the RAF in March 1943, undertaking his Flight Training at Rissington (where he ‘wrote off’ an Aircraft), Ansty, Oakesfield, Dewinton and the United States Naval Air Station at Grosse. Throughout his training, and despite his accident, he obtained ratings from his Instructors ranging from ‘average’ to ‘high average’. He was Commissioned in September 1944 and granted his permanent Commission in October 1948. He had been at Kinloss for over 2½ half years, having been posted there in November 1947, and by the date of the fatal crash had logged over 1300 flying hours. At age 25, he was the youngest of the Flying Instructors on the Station and was regarded as an excellent Instructor with the ability to impart knowledge with clarity and ease. Flt Lt Williams was widely experienced in Coastal Operations, particularly in the development of anti U-Boat weapons, having been on the Staff of the Anti-submarine Warfare Development Unit prior to his posting to Kinloss. For a considerable period of time, he combined his instructional duties with those of Intelligence Officer at 236 OCU, a role he had only recently given up. He was also in charge of the Sailing Club – as a keen yachtsman he was highly regarded at the nearby Findhorn Yacht Club. He was also well known in the area for his choice of Automobile, a Vintage 1923 Rolls Royce Touring Car, which was often to be seen on the local roads. At the time of the fatal crash, Flt Lt Williams was occupying the 2nd Pilot’s Seat in the Lancaster. He was pronounced dead at the scene of the accident from severe burns. Unmarried, and having lost his only brother in WW2, he was survived only by his widowed mother. The funeral took place at nearby Kinloss Abbey on Monday 16th January, with the cortege led by Squadron Leader A L J Craig and a Guard of Honour. The Station Pipe Band played as the procession moved at the slow march, and the service was conducted jointly by Padre Jamieson from the Station & Canon Lake from Forres.

Nav 2 John Cunningham (Navigator)

Service: Royal Air Force – Service Number: 1671629

Unit: 236 OCU, RAF Kinloss

Date of Birth: 21st February 1923 – (Date of Death: 12th January 1950)

Buried: Jarrow Cemetery, Co. Durham

John Cunningham joined the Royal Air Force in 1941 and served throughout WW2 in Bomber Command as a Navigator. He originally went to RAF Kinloss as a Trainee on a Conversion Course in June 1948, and on completion was posted to 120 Squadron, Anti-Submarine Warfare Specialists. However, his skills as a Navigator led to him returning to 236 OCU as an Instructor in February 1949. Nav 2 Cunningham was known as a quiet and unassuming man, an excellent Instructor, and at all times thoroughly dependable. At the time of the crash, John Cunningham was occupying the Navigator’s seat in the Lancaster. During the search for Survivors, his body was overlooked as it was beneath the remains of the Port Wing and he was initially listed as missing – he was discovered the following morning and his body moved to the Station Mortuary alongside his Crewmates. It was believed that he had died instantly from a fractured skull & multiple injuries. Nav 2 Cunningham had been due to leave the Royal Air Force a few weeks later, on termination of his engagement in the Force, but he had let it be known that he was thinking about staying on for another Period. Survived by his wife and son Leonard, John Cunningham was buried at Jarrow Cemetery, County Durham.

Flt Lt Leslie George Harris DFC (Pilot)

Service: Royal Air Force – Service Number: 173753

Unit: 236 OCU, RAF Kinloss

Date of Birth: 21st March 1922 – (Date of Death: 12th January 1950)

Buried: Crayford Churchyard, Kent

Flight Lieutenant Harris had 1st been Posted to Kinloss in 1947 after serving in Coastal Command throughout WW2, and by 1950 he was the longest-serving Instructor on the base and had logged more than 2000 hours flown. In addition to being a Flying Instructor, he was also a Training Officer to the Squadron, being responsible for drawing up flying programmes and the training record of all Courses passing through Kinloss. He was also Station Athletics Officer, as well as being Entertainments Officer for the Officers’ Mess. It is recorded that in all these duties he always showed unfailing energy and enthusiasm, consistent cheerfulness in the face of all difficulties being his outstanding characteristic. Flt Lt Harris had joined the RAF in 1939, serving 1st as an NCO Pilot before being Commissioned in March 1944 (he was granted a permanent Commission in 1948). His Initial Training was carried out at Finningley in Yorkshire, with more advanced training at Little Rissington, and also overseas at the United States Naval Air Station at Pensacola. On operations, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross after ditching his aircraft in the Bay of Biscay while taking part in anti U-Boat operations. He successfully ditched in rough seas, and he and his 4 Crewmen survived many days adrift in a rubber dinghy without any food or water until, when the search for them was on the point of being abandoned, they were picked up in an exhausted condition by a British Destroyer. The survival of the Crew was due to the excellence of his leadership and to the inspiration of his example. After this hazardous experience, he insisted on returning immediately to full Operational Duty without any rest to recover from the trials he had endured. When Lancaster SW363 crashed on the night of 12th January 1950, Flt Lt Harris was at the Controls in the 1st Pilot’s seat. He was the only member of the Crew known to have survived the initial impact and the fire, but died from multiple injuries and shock shortly after being placed into an Ambulance at the Crash Site. A spokesman from RAF Kinloss stated that he was universally popular with Officers & Airmen; his loss on the Squadron, and in the Mess, was very great and his death would be deeply felt by all who had worked with him. Leslie Harris was interred at Crayford in Kent and was survived by his wife and one child.

Flt Lt Alfred Enos Stephens (Flight Engineer)

Service: Royal Air Force – Service Number: 1766162

Unit: 236 OCU RAF Kinloss

Date of Birth: 26th June 1920 (Date of Death: 12th January 1950)

Buried: St Mary’s Burial Ground, IoW

Alfred Enos Stephens joined the Royal Air Force in June 1940, serving 1st as a Fitter and later as a Sergeant Flight Engineer. He was posted to the West Indies as an Instructor, and his exceptional abilities as a Lecturer & Instructor led to him being granted a Commission in April 1944. He remained in the West Indies for 4 years and was then posted back to the United Kingdom where he met the woman who would become his wife, a Flight Officer in the WAAF. They married in September 1947. Mrs Stephens resigned her Commission a year later, shortly after her husband was Posted to RAF Kinloss in September 1948, and joined him at Forres. Flt Lt Stephens was regarded as one of the foremost Flight Engineers, well known throughout Coastal Command, with few equalling his knowledge of and ability with, Aircraft Engines. He was also one of the early Editors of the Royal Air Force Magazine that was published in the local Forres, Elgin & Nairn Gazette. At the scene of the crash that killed all 5 Crew members of Lancaster SW363, the body of Flt Lt Stephens was found alongside that of Flt Lt Williams. Both were lying forward and slightly to the right of the main Wreckage, and Stephens was judged to have died from multiple injuries. He was interred at St Mary’s Burial Ground at Cowes, Isle of Wight.

Photographs were taken at the scene of the Crash of the Lancaster, plus a photograph used at the Board of Inquiry showing the recovered faulty fuel filler cap from the Port Wing. It can clearly be seen from some of these pictures that the Engines were not under power at the moment of impact – the way the propellers had bent, and the lack of furrows on the ground surface indicated to the Examiners that they had all been shut down before the Aircraft hit the ground.

Similar Accident Halifax Bomber – Linton on Ouse

On 13th January 1941 this brand-new Aircraft was being given a Fuel Consumption Test and carried a mixed Crew but all were operationally experienced and qualified to carry out the Test. They were to carry out the test at 12,000ft at which they were to cruise at that height for an hour and measure the Fuel Consumption. The Aircraft took off from Linton on Ouse at 11.20hrs and climbed away. About half an hour later the Aircraft was seen near Dishforth at around 3,000ft with the Port undercarriage down and a trail of vapour behind the Port side of the Aircraft. One of the Port Engines was also seen not to be working. The vapour then ignited (probably as a result of being ignited by an Engine exhaust flame) and a large fire was seen on the Port side of the Aircraft after which the Aircraft entered a steep dive before crashing from 2,500ft near Baldersby St James, between Thirsk & Dishforth at 11.53hrs. All the Airmen on board were sadly killed instantly. The fire was thought to have burnt away the Aircraft’s tail control surfaces making the Aircraft become uncontrollable. The Crew were found to have all been wearing their Parachutes and all were probably preparing to bale out when the Aircraft entered the spiralling dive and as a result, they were unable to get out.

The cause of the fire was blamed on the failure of the Ground Crew at Linton on Ouse to put the fuel-filler cap back on one of the Port fuel tanks after it had been refuelled. The vapour seen behind the Port Wing would also certainly have been fuel, which, by the time it ignited had soaked into the tail section of the Aircraft. Also of note is that the Port outer Engine had been suffering trouble since its delivery. It suffered a coolant leak on 3rd December 1940 which resulted in a new Radiator being fitted and then the same Engine showed low oil pressure, it was run-up on 24th December 1940 and a new oil relief valve had to be fitted. Following the crash, all the Engines were removed and taken away for inspection and this Engine was found to have suffered an oil shortage in the air prior to the Crash, part of the Crankshaft had broken causing the failure of the Engine. Further investigation of other early Halifax’s found that this was a design problem with early Halifax’s. When full of fuel and in a tail-down position the oil pumps on the outer Engines were above the oil level. This oil system was later changed to stop the problem re-occurring. Why the undercarriage had dropped or been lowered is not known.

Similar Tragedy

RAF Avro 683 Lancaster G.R.III/TX264, BS-D

(A Type B.III bomber modified for maritime reconnaissance purposes.)

Aircraft of the period were an inspiring sight and the Lancaster Bombers of WW2 are remembered as one of the historical components of the Air War. Today Aircraft enthusiasts use 401K business funding flying replica Aircraft and collecting historical artefacts relating to Aircraft of the time period. The Lancaster was an iconic sight in the skies of the time. Aircraft Type Nicknames: “Lanc”; “Lankie” The Avro Lancaster was designed initially as a Heavy Bomber. It was developed from the Avro Manchester Bomber, but the unreliable Rolls-Royce Vulture Engines of the Manchester were replaced on the Lancaster with 4 Rolls-Royce Merlin Engines. However, the Lancaster GRlII variant featured here was fitted with 4 American-built Packard Merlin Engines.

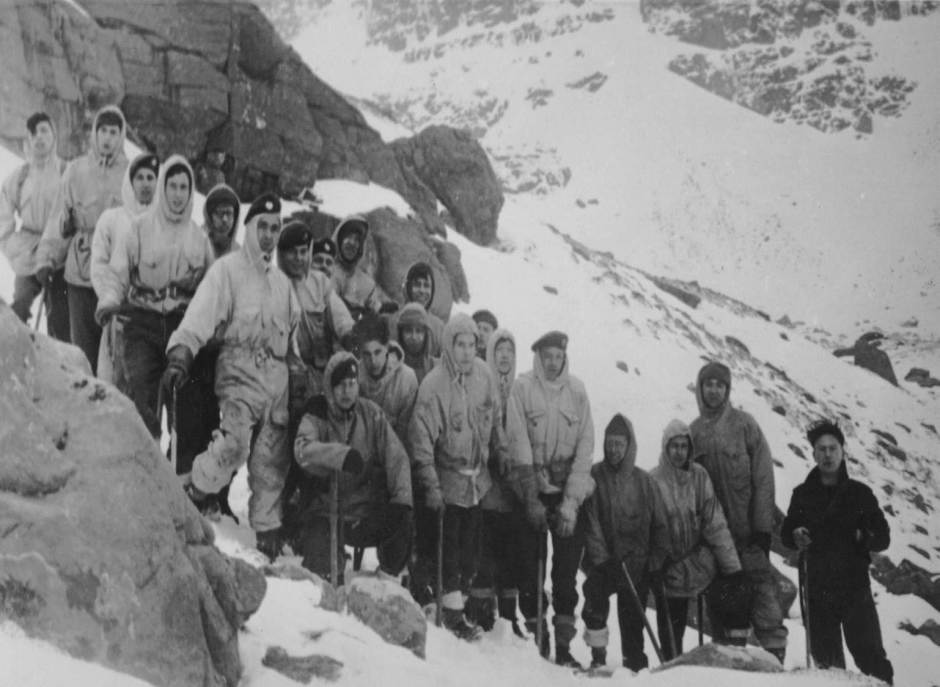

In the evening of the 13th of March 1951, this Lancaster set out from RAF Kinloss for a training flight and a Navigational Exercise. The Aircraft was on the final leg of a night-time Navigation exercise between the Faroes & Rockall and was heading home when it collided into the Mountain, Beinn Eighe, at around 02.00hrs on the 14th of March. (Massif summit 3258ft) It was only 30 minutes from landing back at Base. the Lancaster Crashed just 4.6M (15 feet) below the Summit.

Although experienced Civilian Mountaineers offered their services to find the Aircraft, the RAF declined their assistance initially. This was unfortunate, as, unlike today, and unlike the Civilian Mountaineers of that day, RAF Recovery Teams were not fully Trained or Equipped for arduous mountain rescues or recoveries. Indeed, it was as a result of this incident that the modern RAF Mountain Rescue Teams (RAF MRTs) were formed.

Kinloss Battle HQ was constructed to defend RAF Kinloss during WW2, and is still present on the site (2009), within the perimeter of the modern-day RAF Airfield & Base. The structure follows a standard design pattern, known as 11008/41. The purpose of the Battle HQ was to deny the use of the Airfield to the Enemy in the event of Invasion. Sited to provide good coverage of the Runways, the Battle HQ was heavily reinforced to resist attack by Enemy Troops which may have been parachuted in to take over the Airfield, it was provided with a concrete roof over 2ft thick, and underground rooms for the defenders. The only features visible on the ground are the raised observation post and the entrance, which lies in the ground a few metres away from the post. The Observation Post is well preserved, and lies to the South-east of the Runways, hidden within a small plantation which has become established around it since the end of the War. Originally, it would have been in the clear and been only a few metres to the East of the Airfield perimeter road, and the Eastern end of the original Northwest-Southeast Runway. Also reported nearby are trenches for defenders, & machine-gun emplacements. As with the HQ, these are now lost within the later trees. Reported to have been inspected and recorded before being closed, the entrance & emergency exit have been plated and sealed by the MoD. There is no public access, as the structure lies within the perimeter of an active RAF Base. The photograph clearly shows the emergency exit hatch located immediately adjacent to the Observation Post, and the normal entrance/exit located on the ground nearby. The plating added to seal the facility is also clearly seen.

Kinloss Battle HQ was constructed to defend RAF Kinloss during WW2, and is still present on the site (2009), within the perimeter of the modern-day RAF Airfield & Base. The structure follows a standard design pattern, known as 11008/41. The purpose of the Battle HQ was to deny the use of the Airfield to the Enemy in the event of Invasion. Sited to provide good coverage of the Runways, the Battle HQ was heavily reinforced to resist attack by Enemy Troops which may have been parachuted in to take over the Airfield, it was provided with a concrete roof over 2ft thick, and underground rooms for the defenders. The only features visible on the ground are the raised observation post and the entrance, which lies in the ground a few metres away from the post. The Observation Post is well preserved, and lies to the South-east of the Runways, hidden within a small plantation which has become established around it since the end of the War. Originally, it would have been in the clear and been only a few metres to the East of the Airfield perimeter road, and the Eastern end of the original Northwest-Southeast Runway. Also reported nearby are trenches for defenders, & machine-gun emplacements. As with the HQ, these are now lost within the later trees. Reported to have been inspected and recorded before being closed, the entrance & emergency exit have been plated and sealed by the MoD. There is no public access, as the structure lies within the perimeter of an active RAF Base. The photograph clearly shows the emergency exit hatch located immediately adjacent to the Observation Post, and the normal entrance/exit located on the ground nearby. The plating added to seal the facility is also clearly seen.